Paul Reynaud

“I have lost my country, my honor, and my love.”

Jean Paul Reynaud was born eight years after the Republic he would see fall, on 15 October of 1878. He was one of four children born to a local textile magnate in the commune of Barcelonnette in the French Alps, resulting in a fairly comfortable upbringing by a family that also boasted political connections. Moving to Paris at the age of five with his family, Reynaud would eventually attend law school, graduating and entering into practice in the French capitol. In 1912 he would marry Jean Henri-Robert, who would give birth to a daughter two years later.

His first foray into politics came in the immediate aftermath of the Great War, being elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1919 for his hometown, starting a career as a conservative politician in the turbulent world of interwar French politics. He would eventually shift more towards the center, and would make a name for himself for his softer stance toward Germany, something of an aberration in French politics of the time. As his career progressed, he would show a knack for economics and would hold various ministerial positions in the 1920s and early 1930s following a move to Paris.

Reynaud clambers from an aircraft upon his return to Paris after a visit to Indochina in 1931

Reynaud would hold the posts of Minister of Colonies, Minister of Finance, Minister of Justice and even Deputy Prime Minister as the 1920s gave way to the Great Depression of the 1930s, and it was during this time that his reconciliatory stance toward Germany hardened. This change of heart came about first due to the increased urgency of reparation payments to bolster the French economy, and was subsequently reinforced after the Nazi seizure of power ensured that Germany once again posed an existential threat to France and the European order as a whole. His policies for correction of the economic crises of the decade would, however, lead to alienation from his party, in particular over the devaluation of the Franc. During this time Reynaud would make the acquaintance of an ambitious Army officer by name of Charles de Gaulle, and would come to support his advocacy for mechanized warfare as opposed to the static defensive doctrine that spawned the Maginot Line along the Franco-German border.

Reynaud giving a speech in 1932 during his Deputy Premiership

By the late 1930s Reynaud had become a staunch opponent of Hitler’s new order in Germany, and was a vocal opponent of any type of concession or appeasement of Germany, and this combined with his economic stances to ensure that he was sidelined within his own party for most of the decade, not holding any ministerial positions between 1932 and 1938. He had, however, been keenly observing the situation and making contacts, including with British politician Winston Churchill, who shared his strong distrust of the Nazi regime in Germany and beleived that both of their respective nations needed to prepare for another European War.

In 1938 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier met in Munich for a conference with Hitler over the German demands for control of the Sudetenland (the Czech-German border region), notably excluding Czechoslovak President Edvard Benes from the meeting that would decide the fate of his nation. During this conference the two Western powers caved to the Fuhrer’s demands, effectively casting Czechoslovakia to the wolves, and a disgusted Reynaud, recently appointed as Daladier’s Minister of Justice, threatened to resign in protest.

Prime Ministers Chamberlain and Reynaud with Hitler after signing the Munich Agreement

German Federal Archives

Convinced to remain in the government, he left his party to operate as an independent, and was appointed Finance Minister in November of 1938 with a mandate to reform the French economy to prepare for war. This was accomplished by a series of radical deregulation efforts, including the abolition of the forty hour work week and forcefully breaking strikes while sounding the alarm about his country’s poor state of readiness for the now inevitable conflict. Despite the resulting economic growth, within a year that war came to France following Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1 September of 1939.

During the first few months of the Second World War Reynaud continued in his role as Finance Minister, while the conflict festered in what was known as the “Phony War”. This continued through the Finnish-Soviet Winter War, in which heavy debate existed over sending Allied aid to the Finns before the brief conflict ended with no action by the western powers, and in turn resulted in the collapse of Daladier’s government for perceived inaction. On 21 March, 1940 French President Albert Lebrun named Reynaud as the new Prime Minister of France after an electoral victory by only a single vote margin in the Chamber of Deputies.

Reynaud (fourth from left) with members of his new cabinet shortly after becoming Prime Minister

Shorlty after taking the reins of power in France Reynaud made a joint declaration with Britain’s Chamberlain against either nation accepting a separate peace, and recommitting to the war against Germany. Internally, however, the French government was fragmented, with serious debate regarding the primary effort of the war be directed against Germany or the more distant USSR. Despite pressure to focus on the Soviets, Reynaud joined the British in sending an expeditionary force to aid Norway following the German invasion of the country in April of 1940, finally taking an active role in fighting the young war.

The state of equilibrium that the war had been in since its inception along the Western Front was shattered on 10 May of 1940, as the Germans launched their invasion and instigated the Battle of France. Almost immediately, the Anglo-French plan to meet the invasion began to fall apart, as the German’s mechanized formations broke through the weaker French lines at Sedan and began to flood into the interior, even as the bulk of the Allied force attempted to meet the expected German thrusts further north in Belgium. The sluggish response to the breakthrough led to Reynaud removing Commander in Chief General Maurice Gamelin from command and replacing him with Maxime Weygand, while at the same time recalling the Great War hero, Marshal Philippe Petain, to serve as his Deputy Premier on 18 May. He likewise took over the position of War Minister from Daladier (who had held it since his dismissal from Premiership) in addition to his duties as Prime Minister.

Reynaud with Marshal Petain and General Weygand during the critical moments of May, 1940

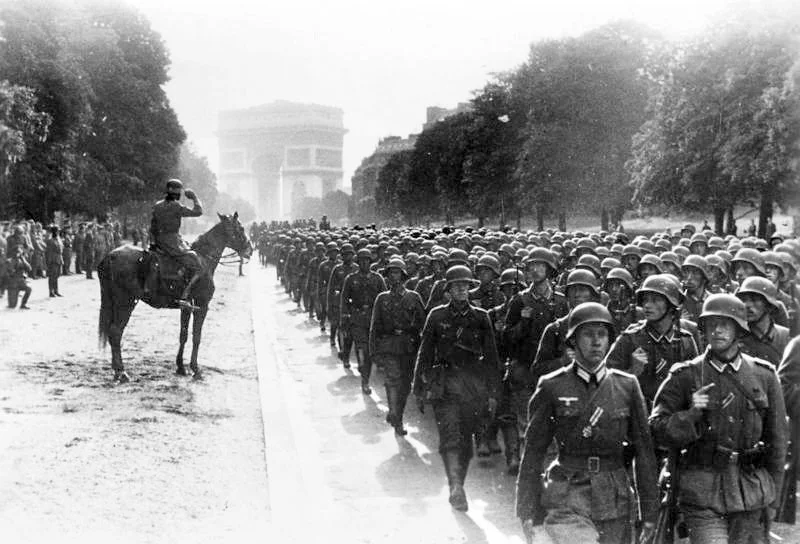

Despite these changes, it was too late to prevent the envelopment of the Allied armies in Belgium, prompting a seaborne evacuation via the port of Dunkirk, which was completed on 4 June. The Germans, for their part, commenced the second phase of their offensive against France the following day, and although initially Weygand’s armies were able to stall the onslaught, on 10 June Reynaud was forced to declare Paris an open city and evacuate the government to Bordeaux. The capitol fell on 14 June, the day after a despondent Reynaud met with Churchill in Tours, where the British leader was alarmed that only General de Gaulle (now Undersecretary of War) seemed to be determined to carry on the fight, with Petain and Weygand heavily pressuring Reynaud to sign an armistice with the Germans. Italy’s entrance into the war on 10 June had prompted more panic within the French government, and by this phase Reynaud’s confidence was collapsing. He had, in fact, attempted to resign on 13 June, but this had been rejected by President Lebrun.

German troops parade in Paris after the fall of the city

German Federal Archives

Faced with a collapsing army, strong internal pressure for armistice, and a lack of assistance from British or American outlets, Reynaud resigned from office on 17 June of 1940, with Marshal Petain replacing him. Petain signed an armistice with the Germans five days later at Compiegne, site of the signing of the Armistice of 1918, ending the participation of the French Third Republic in the Second World War.

Representative’s of Petain’s government sign the armistice with the Germans

Reynaud plead with Petain and Weygand to continue the war from the colonies, but was rebuffed. With little other choice, he left Bordeaux by car with his mistress Helen de Portes, bound for his summer residence on the French southern coast, with an intention of subsequently fleeing to French North Africa. While en route his car crashed into a tree, killing de Portes and hospitalizing the former Prime Minister with a head wound. After his release, Reynaud announced his retirement, and rejected an offer from Petain for a diplomatic position as Ambassador to the United States.

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, where Reynaud was held by the Germans for several months

This would, however, lead to Reynaud being viewed with suspicion by Petain’s new totalitarian regime in Vichy, and he was arrested in September by Vichy authorities. Unlike many other Third Republic leaders, Reynaud was not placed on trial at Riom in 1942, but was instead transferred to German custody, where he was imprisoned at the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp for several months before being moved to a special prison at Itter Castle in Tyrol along with other top French prisoners, including Daladier, Gamelin and Weygand.

There he would remain for the duration of the war, although his story of liberation was substantially more complicated than the ideal of a friendly soldier throwing open his cell. Finding their SS guards having vacated the castle, the Frenchmen raided the armory and took control of the fortress. Reynaud and a comrade then chanced a stroll into the nearby village, where he observed German troops still active in the area, they elected to remain at Itter and send a runner to make contact with the Americans. This would lead to a sequence of events that saw an American tank detachment joined by a German Wehrmacht unit to defend the castle from a brief siege by SS troops. During this action the French prisoners, including an MP40 toting Paul Reynaud, would take their place on the ramparts to fight off the attack. During the battle the leader of the Wehrmacht unit, Major Joesf Gangl, would fall to a sniper’s bullet while attempting to move to Reynaud’s position.

Schloss Itter, site of the German’s prison for VIP French prisoners

Sammlung Risch-Lau, Vorarlberger Landesbibliothek

Following the Battle of Itter Castle, Reynaud returned to France and immediately to politics, with election to the reconstituted Chamber of Deputies in 1946. His old friend Charles de Gaulle had, of course become the dominant figure in French politics after leading Free France during the war, and he even played a leading role in drafting the constitution of the modern French Fifth Republic in 1958. His alliance with de Gaulle would break just four years later, however, over the issue of electing the President via universal suffrage, which the conservative Reynaud feared was an attempt by the General to consolidate his power. This move and the subsequent electoral defeats he suffered caused Reynaud to retire from politics in 1962.

While he made his return to politics, Reynaud also finally divorced his wife Jean Henri-Robert in 1949, that same year marrying his longtime secretary Christiane Mabire, who would eventually bear three more children. After his retirement Reynaud busied himself with writing memoirs, never quite getting past the trauma infliced on him and the nation by the events of 1940. In 1966, the aged former Premier underwent surgery for appendicitis at a hospital in Neuillt-sur-Seine, whereupon he suffered a cardiac arrest and died at the age of 88. He left behind his second wife, as well as four children, and was buried in his family crypt in Paris.