The Advance on Manila

October 20, 1945 to February 2, 1945

On a bright, warm Hawaiian day in July of 1944, General Douglas MacArthur, now commander in chief of the Southwest Pacific Area, met with US President Franklin Roosevelt, Chief of Staff Admiral William Leahy and Admiral Chester Nimitz, his opposite number in command of the campaign in the central Pacific.

The Pacific Conference in Hawaii. From left to right: General MacArthur, President Roosevelt, Admiral William D. Leahy (Presidential Chief of Staff), Admiral Nimitz

The meeting took place at the mansion of fish packing magnate Christian Holmes on Waikiki Beach in Hawaii, and was to be where the future of the Pacific War was deceided. The two theater commanders, MacArthur and Nimitz, both had differing opinions as to where the next major operation was to take place. Nimitz and the Navy believed the time had come to strike at Formosa (modern day Taiwan), a view that enjoyed a broad support among the top US brass. MacArthur, on the other hand, was adamant that the Philippines must be liberated, both to secure the strategic anchorage at Manila and deny the use of the islands to the enemy, as well as for the political ramifications of abandoning US territory when the ability to liberate it was presented.

With the 1944 Presidential Election in its terminal phases, Roosevelt was apt to consider the political aspects, and the passion with which MacArthur advocated for the Philippine option as opposed to the dry, rehearsed nature of Nimitz’ proposal, won over the President. On July 28th, 1944, MacArthur was ordered to prepare his forces to return to the Philippines.

The Japanese battleship Musashi under heavy air attack in Leyte Gulf

On October 20, 1944 the full might of the United States descended upon the island of Leyte, with a massive air and naval bombardment commencing at 0600, continuing for four hours until the first wave of infantry began their landings at 1000. As US forces made their landing, the Japanese attempted to launch a massive naval counterattack with almost the entire remaining surface fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy. This plan, dubbed Sho-ichi-Go (Victory Plan One), involved using the few carriers remainging to the Japanese as bait to lure the main US naval force, Admiral Bull Halsey’s Third Fleet, away from the Philippines, allowing a pincer attack on the landing area by the IJN’s remaining heavy surface fleet, including the two Yamato Class Battleships, the largest ever built.

The Japanese main forces were detected, leading to them being set upon by US carrier aircraft. In the ensuing attacks, the powerful Japanese Center Force suffered severe casualties and turned back, loosing the Yamato class ship Mushashi in the process. The Southern Force had an even worse experience, with the Battle of the Surigao Strait ending what was to be the last battleship on battleship engagement in naval history with the aged Japanese ships being decimated, leaving only the destroyer Shigure to escape the engagement. The Center Force, however, turned around and traveled through the San Bernardino Strait, approaching a position to engage the Leyte invasion force with only a token US destroyer screen in their way, Halsey’s carriers having departed to chase down the decoy Japanese carriers. The result was the one sided Battle of Samar, previously detailed on this site, which resulted in a US victory despite all odds.

GIs on the beach at Leyte

With the Imperial Japanese Navy now all but destroyed, the invasion was clear to proceed further. The Japanese defense was hampered by the fact that the commander of the Philippines, General Yamashita, had intended to concentrate his forces for the defense of Luzon, but had been overruled on the 22nd by his superiors in Tokyo, ordering him to concentrate all his efforts on preventing the Americans from taking Leyte. In addition, Japanese forces had already been concentrated in Mindanao, as the island’s proximity to the Americans led them to believe it would be the primary target.

US Army

Back on the beaches, the Americans had secured a beachhead in three different areas on the coast of Leyte Gulf, and within an hour heavy equipment was being brought ashore despite enemy resistance. Getting off the beaches, US forces found the terrain a swampy jungle, hampering their movement and aiding the camouflaged Japanese defenders. By evening, the beachhead was a mile deep, and 1st Cavalry troopers were fighting the Japanese on Tacloban Airfield, while other forces had secured the a vantage point at Hill 522. Earlier in the day, just after noon, General MacArthur and his staff, as well as Sergio Osmeña, President of the Philippine Commonwealth, boarded a landing craft to approach the beach new Tacloban. The landing craft bottomed out on its journey to shore, forcing an irritated MacArthur to wade to shore with his entourage. The result was the capture of one the most iconic images of the Second World War.

MacArthur (center) wades ashore at Leyte after his landing craft beached. President Osmeña is also present, wearing the pith helmet at far left

“People of the Philippines, I have returned! By the grace of Almighty God, our forces stand again on Philippine soil.”

The campaign for Leyte would drag on until just after Christmas of 1944, with the Sixth Army being withdrawn from the island in preparation for landing on Luzon in early 1945. The fighting on Leyte had been disastrous for the Japanese, who saw the loss of almost 50,000 troops, and the annihilation of four infantry divisions. More than half of the aircraft available in the Philippines were destroyed, and the Imperial Japanese Navy had been effectively destroyed as an effective force. Even with a quarter of a million men left to him on Luzon, General Yamashita could count on no significant naval or air support against the overwhelming might of the Americans.

The battleship USS Pennsylvania leads the way into Lingayen Gulf

On the morning of January 9, 1945 a column of US warships entered Lingayen Gulf, and commenced a massive bombardment of the local beaches. The Japanese responded with kamikaze attacks, destroying an escort carrier and several other light warships, but the bombardment was not seriously disrupted. The landings began at 0900, with US forces coming ashore at the same spot the Japanese had years earlier, again with almost no opposition.

Japanese aircraft take off from a field in Manila to attack the landings at Lingayen Gulf

US Navy

US landing craft move towards the beach of Lingayen Gulf

As the Americans approached the city, they moved slowly, so slowly, in fact, as to arouse the ire of General MacArthur, who felt that the advance could be faster in the face of limited Japanese resistance. The XIV Corps of General Griswold was ordered to advance southward toward the capitol, its flank screened by the I Corps, encountering only scattered pockets of light resistance. In order to spur on his Army commander, General Krueger, MacArthur moved his command post thirty five miles further forward than Krueger’s, an unprecedented situation. Even while this happened (and gained all the press attention), the I Corps was engaged in vicious combat with Yamashita’s Shobu Group on the approach to Baguio.

US planes attack Clark Field

US National Archives

As the Americans approached the old US Army Air Force base at Clark Field they finally began to encounter significant resistance as the Japanese had dug in to the surrounding hills with extensive tunnel systems, holding up the advance and irritating a MacArthur who was already planning his grand entrance into Manila.

From the first encounter with Japanese resistance outside the airfield on January 23rd, it would take over a week to finally reduce the Japanese stronghold, with troops forced to clear the Japanese out of extensive tunnel systems with flamethrowers. Having overcome the worst resistance there, the 37th Infantry continued to drive on Manila starting on February 2, rapidly approaching the northern suburbs.

On January 27th, 1945, the 1st Cavalry Division landed at Lingayen, and began advancing toward Manila, after a still-impatient MacArthur ordered them to advance on Manila as fast as possible. They formed a “flying column” of fast vehicles and troopers and began a rapid drive on the city under the command of Brigadier General William Chase.

General Verne Mudge, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, speaks to Brigadier William Chase aboard his Sherman during the drive on Manila

The flying columns made their rapid advance on the city, supported by US Marine Corsair fighter bombers against scattered Japanese resistance, moving rapidly and essentially racing the 37th Infantry to Manila, but the more streamlined and fully mechanized cavalry units had a significant advantage over the infantry. But even then, another operation was in play, this time to the south: General Robert Eichelberger’s 8th Army was landing south of the city at Nasugbu, and the 11th Airborne Division was preparing to drive on the city with part of its force, to be joined by the rest after a drop on Tagaytay Ridge.

Filipino guerillas sail to meet the 11th Airborne as they approach Nasugbu

US Navy

They had quickly begun their advance from the beachhead, eliminating only scattered enemy resistance and pushing toward Tagaytay Ridge, where they ran into stiff Japanese opposition as they approached a grouping of mountains defended by the IJA’s Fuji Force. After securing the first Japanese position on Mount Aiming, the paratroopers held it against infantry counterattacks, with other elements attempting to dislodge the IJA from Mount Batulao and Mount Cariliao, where the dense jungle made movement difficult and the airborne suffered from a lack of heavy artillery to counter larger Japanese guns. On February 2, Mout Cariliao was finally secured, but Japanese resistance continued overnight on Mount Batulao. With these obstacles overcome, the Japanese defenses on Tagaytay Ridge proper were all that remained in the path of the 11th Airborne and Manila, and the planned parachute drop on the ridge by the remainder of the division was set for February 3.

11th Airborne paratroopers march through Nasugbu

Under the Boot of the Empire

A Japanese soldier stands guard at a roadblock along Bugos Street in front of the Legislature Building

After the fall of the American backed Commonwealth, the Japanese had placed a military administration in control of the islands, assisted by a collaborationist government. At first propaganda had pushed the concept of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”, portraying themselves as liberators of fellow Asians from the yoke of Western imperialism. This program included adding Japanese language curriculum to schools, as well as an altered, pro-Japanese history. A new Peso was issued, under the control of the occupation authority and thus subject to the whims of Tokyo, and it began to rapidly inflate.

In 1943 the Japanese allowed the establishment of a puppet regime, the so-called Second Philippine Republic under President Jose Laurel. This government, led by the KALIBAPI party, furthered the goals of the Japanese occupation, but now with a veneer of local support. KALIBAPI also raised a militia to enforce its aims, and this organization, known as the Makapili, was greatly feared by the civilian population, although they were less effective against the guerrillas they were intended to oppose.

A letter mailed in the Philippines under the Japanese occupation, bearing censorship stamps

In the city of Manila itself, the activities of guerillas were less widespread, but civil disobedience and passive resistance would prove to be a long term problem for the occupiers. Japanese officers transferring to the city would often fall prey to having their boots shined by children on the streets, not knowing that the banana peels used to make the polish would attract hordes of flies around the officer until he realized the issue. Petty theft was commonplace, with even the swords of Japanese officers occasionally being stolen.

The Japanese took complete control of local media, with radio stations and newspapers being subject to strict censorship, and when executives objected they were often arrested and interned. Filipinos were required to bow to every Japanese soldier they passed in the street, and even the most minor infractions by civilians were met with physical violence ranging from a backhanded slap to beatings.

A Japanese soldier posts instructions on basic Japanese for civilians

In addition to the more direct problems caused by the presence of Japanese troops, the policies of the Imperial Japanese Army authorities as well as the puppet Republic set up under Jose Laurel led to further problems, most notably economic in nature. The Japanese began to issue their own version of the Peso, outlawing the use of the Commonwealth currency. This shift from the silver standard to a fiat currency controlled by the occupiers led to various issues, particularly as the new government and the Japanese attempted to exert control by printing vast quantities of money for their use. The resulting hyperinflation exacerbated issues leading from a significant shortage of consumer goods and food, and by late 1944 a small sack of rice cost an average of

₱5,000.

The looting in the final days before the Japanese entered Manila had caused a glut in the food supply, but this was followed by a perpetual shortage that came as a result of the disruption of the planting season during the Japanese invasion, and furthered by guerilla activities and (later in the war) by US submarines preventing the importation of foodstuffs and consumer goods.

A Japanese issued five Peso note, overstamped with an American propaganda slogan

As the Americans approached, a flurry of activity was taking place. The puppet government had been evacuated to Baguio, although since the declaration of martial law in late 1944 it had lost any real semblance of authority anyway. Meanwhile, the Japanese were preparing to evacuate the city in compliance with the orders of General Yamashita. Engineers were preparing bridges for demolition, and convoys of trucks were removing the vast quantities of supplies located in the port warehouses to support Shobu Group’s stand to the north. Yamashita, concerned over the need to feed the civilians in a state of siege, also felt that making a stand in an urban environment would be counterproductive to his plans to hold on in the north, not to mention the effect of the hostile attitudes of much of the populace.

The Imperial Japanese Army was still in the process of evacuation when the Americans neared, and scrambled to remove the last of their supplies and equipment from the city. But Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, commander of the 31st Naval Special Base Force, had other intentions. This unit of the Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF, essentially Japanese marines) was under the control of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and although Iwabuchi was nominally under the control of Yamashita, as overall commander in the Philippines, interservice rivalry was fierce in Imperial Japan, and Iwabuchi greatly resented taking orders from an Army officer. In addition, Iwabuchi felt that as one of the best harbors in the Pacific, Manila needed to be vigorously defended. He argued with Yamashita over the wisdom of abandoning the city, but eventually was overruled and instead left to command the garrison as it completed it’s duties to deny valuable infrastructure to the Americans.

Civilian laborers are forced to build barricades on Escolta Street

In order to accomplish his objective, Iwabuchi combined his SNLF troops with the small Army contingent left in the city, as well as large numbers of ad hoc formations composed of Naval administration personnel and the crews from the large numbers of ships disabled in the harbor. In total, he was able to gather approximately 17,000 men for his Manila Naval Defense Force (MNDF), and set about fortifying the city.

Iwabuchi’s troops were under orders to prepare the main bridges for demolition, as well as prepare to destroy the dock facilities in the port. This they did, along with more substantial fortifications. The palm trees lining Dewey Boulevard were chopped down to allow it to be used as an emergency airstrip, and using the logs to barricade streets and construct earthworks in the parks. Rails from the streetcars are placed into holes drilled in the pavement to create tank traps, backed with barricades made with the cars themselves, as well as civilian automobiles and barbed wire. Landmines of all types were deployed across the city, including improvised versions consisting of depth charges and aircraft bombs fitted with pressure detonators and partially buried. Naval guns and anti-aircraft cannons, stripped from the disabled ships in the harbor, were emplaced around the city as well, and incendiary plans are set in motion to begin burning large sections of the city.

With the landings of the US 11th Airborne Division at Nasugbu on January 31st, Admiral Iwabuchi believed that this was intended to be the main thrust into Manila, and began to fortify the southern approaches to the city, creating a series of strong fortifications called the Genko Line, which ran from Manila Bay to Laguna de Bai. It consisted of a series of pillboxes armed with machine guns, naval guns, and anti-aircraft cannons, with it’s core being Nichols Field and Fort McKinley. In addition to this strong defensive position, Iwabuchi issued orders for the old walled city, Intramuros, to be fortified, resuming its ancient role as a citadel. Finally, the reinforced concrete government buildings, such as the City Hall, Finance Building, Central Post Office, Agriculture Building, and Legislature Building were to be turned into fortresses, with the strong walls and open plazas around them making them natural defensive strongpoints.

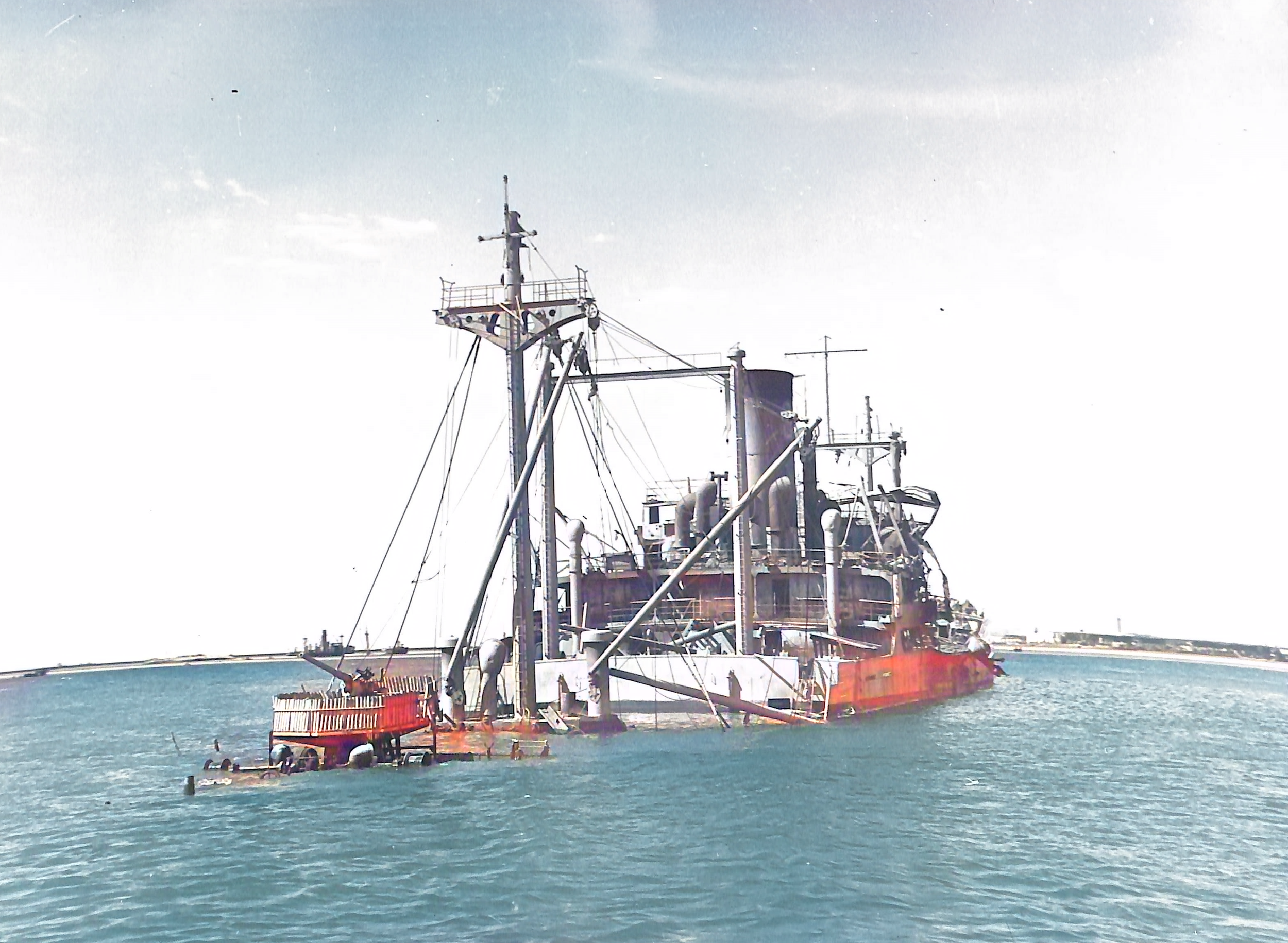

A Japanese ship sunk in Manila Bay, with its anti-aircraft guns still operational

As Iwabuchi prepared for the defense of the city, one problem that presented itself for his intended fight to the death was the lack of small arms. The small Army detachment were experienced infantry, as were his 31st Naval Special Base Force, but the vast majority of his command consisted of naval crews and administrative personnel who were untrained in ground combat and often unarmed. The solution, however, was readily available, in the form of the vast stocks of American weapons and munitions captured when the archipelago fell, most of which were stored in Manila. These stocks were opened, and the weapons distributed to the Japanese sailors of the MNDF.

As the Americans approached the city from both the north and the south, MacArthur’s expectation of Manila being declared an open city, as he had done in 1941, would come to nothing. Admiral Iwabuchi and his troops intended, regardless of the wishes of General Yamashita, to fight to the death over every inch of the Pearl of the Orient.