The Battle of Aachen

Chapter 39

“My captain walked by me, patted me on the shoulder, and said, ‘How are you doing?’ He got about 10 feet from me and got a bullet in his head.”

12 September - 21 October, 1944

As the fall of 1944 began the Allied armies in the west found themselves along the Franco-German frontier. The disaster of Market-Garden was not yet commenced when the Americans arrived at the strong defenses of the German West Wall, known to the Allies as the Siegfried Line. This consisted of hundreds of miles of bunkers, trenches and tank obstacles, constructed before the war to face the French Maginot Line and all but abandoned from the Fall of France in 1940 until the late summer of 1944. A frantic reactivation program was instigated in July at the order of the Fuhrer, although much of it was obsolete or in poor repair.

A patrol reports to an officer at a Siegfried Line bunker near Aachen

The logical path of advance for the Allied armies into Germany was directly through the area just south of the Franco-Belgian border around the old capitol of the Holy Roman Empire; the city of Aachen and the adjacent Hurtgen Forest. The area, known as the Aachen Gap, was a valey with relatively open terrain that could allow for a clean drive into the Ruhr if secured. The city, as the capitol of the “First Reich” in Nazi propaganda, was of extreme political value, and Hitler took a personal interest in its defense. Fortifications were constructed and preparations for urban battle were commenced, as well as orders for the evauation of the city’s civilian population. The commander of the German garrison, General der Panzertruppe Gerhard von Schwerin, recognizing the futility of holding the city with his decimated force recently withdrwan from France, prepared to abandon Aachen to the Americans, but his written orders to that effect were intercepted by the Gestapo, leading to the General’s arrest and replacement. Aachen would be defended to the last.

American GIs along a road near Aachen

Additional German forces were transferred into the Aachen sector from wherever they were available, but despite this as the Americans reached the Siegfried Line positions outside the city, they found them mostly abandoned. The American plan of operations for the Aachen sector was to drive around the city to the north and south, enveloping it and allowing for the relatively easy reduction of the fortified city. Two corps, one each for the northern and southern wing, of the US 1st Army would perform this maneuver, and once this was completed the US 1st Infantry Division would be tasked with securing the city proper.

American soldiers at the edge of Aachen

Defending the city and its sector was the German LXXXI Corps, with four divisions including the 246th Volksgrenadier Division that was deployed inside Aachen as the city garrison. Like much of the Wehrmacht at this phase of the war, these units were understrength, and berift of heavy weapons with which to counter the American armor.

US M10 tank destroyers in the suburbs of Aachen

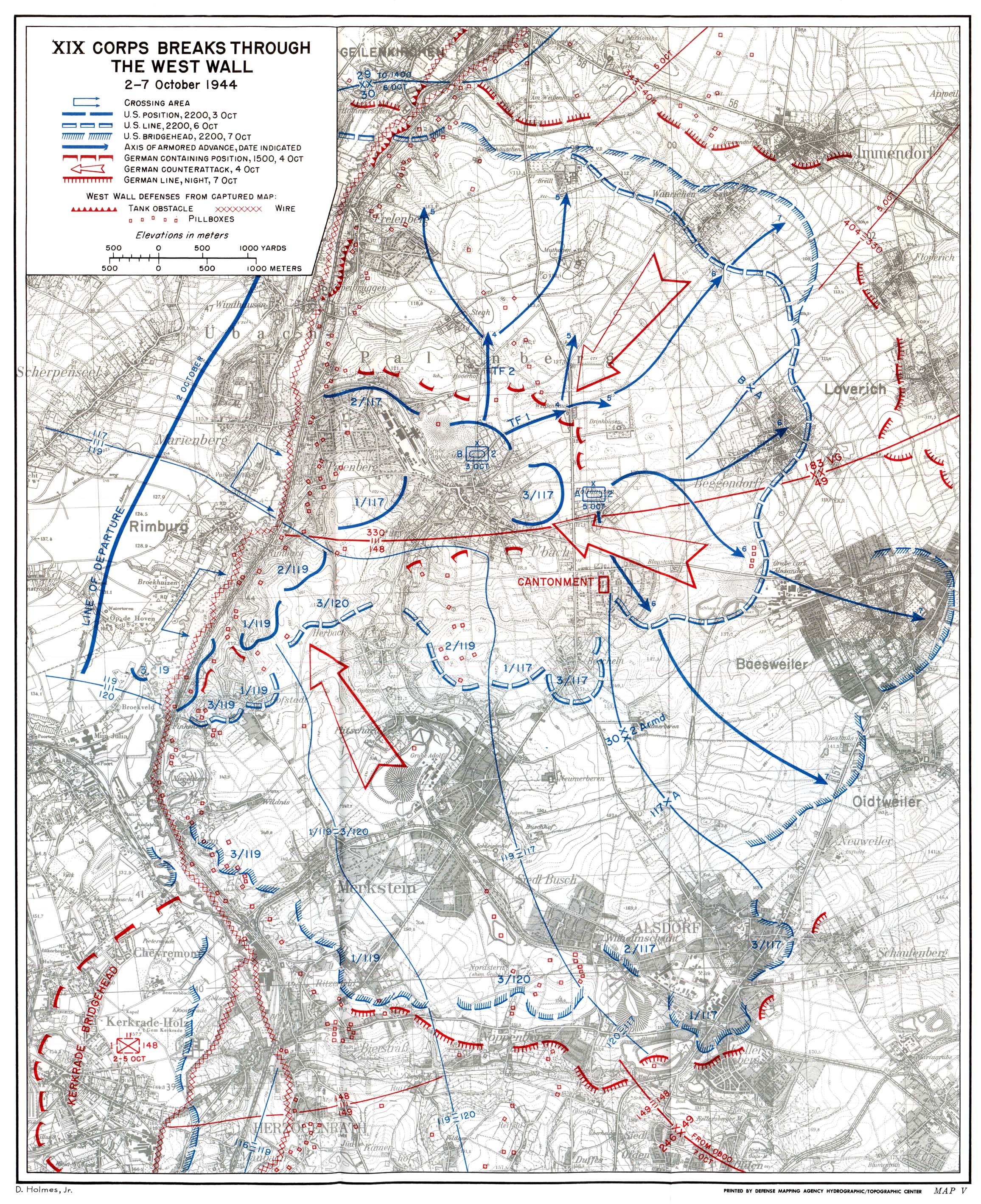

The Americans made their move on 12 September, breaching the weak defenses at the Siegfriend Line, with only some of the strongpoints offering notable resistance. Several strong counterattacks were also launched by the Germans around Aachen, but these succeeded only in slowing the American advance, not halting it. Fuel problems hampered the offensive almost as much as the Wehrmacht, as the long supply lines across France were stretched to their limit since the Normandy landings, and the large allocation of Market-Garden further complicated matters. By the end of September, the offensive was paused, allowing supplies to catch up but also allowing the Germans to additonally reinforce the area.

American troops enter Aachen

Offensive operations resumed at the start of October, as the Americans again made their push to envelop the ancient capitol. Pushing through the defenses of the Siegfried Line, the Americans were forced to move rapidly, as they found that as soon as any position of the line was overrun the Germans attempted to counterattack, requiring the Americans to maintain constant pressure. As the fall weather deteriorated the ubiquitous Allied close air support became less common, and the tanks and self propelled guns the Americans were using to blast away strongpoints became bogged down in the mud of the battlefields.

American tanks enter the city after engineers blast through the rubble blocking access via the city’s railyards

By 10 October, the city was nearly enveloped, with only a narrow corridor still existing for the Germans to access the city. A demand was issued for the capitulation of the garrison, but this was ignored. The following day a large scale air and artillery bombardment of the ancient city began, and two days and 5,000 shells later the Americans commenced urban assault against the city.

US armor on the streets of Aachen

One regiment of the 1st infantry Division led the assault into the city, engaging in room by room fighting against entrenched defenders. The Americans were experienced veterans of the campaigns in France, which gave them an advantage against the German Volksgrenadiers, the vast majority of which were inexperienced conscripts. At the same time as the American assault commenced, the Germans placed Oberst Gerhard Wilk into command of the garrison.

A GI assists an elderly civilian in evacuating the fighting in Aachen

Heavy, close quarters fighting ensued as the Americans entered the city through the industrial area on its southeast side, charging over a railroad embankment and assulting with support from a group of Sherman tankls. Engaging in hand to hand combat within foundries, factories and underground utility tunnels progress was slow and bloody. As the Americans advanced into the narrow, medieval streets, they found themselves being attacked from the rear by German squads moving through the city’s sewer tunnels. This forced the attackers to slow their advance as they systematically blocked and sealed each entrance they encountered in order to protect their flanks.

Tank destroyers engaging a German strongpoint in Aachen

The infantry crawled through the streets with their Shermans, as well as an M12 self propelled 155mm heavy howitzer, which was used in direct fire against German positions in the masonry srtuctures that made up most of the city. This weapon proved quite potent, although the crew was almost entirely exposed atop the vehicle, with constant danger posed by German troops in the apartment blocks that lined the streets. The Germans continued to offer stubborn resistance as the Americans pressed forward, counterattacking with infantry and armor and sometimes temporarily halting the attackers.

An American soldier takes aim at the Germans, covering behind a wrecked flak gun

By 16 October, the American forces operating outside of Aachen linked up, finally closing the encirclement of the city. Left now to hold their shrinking perimeter with only a few StuG assault guns and the renmants of the Wehrmacht, SS and Volkssturm units within them, it was apparent by now that the defense of Charlemagne's city was doomed. Fighting on the streets remained brutal, with flamethrowers joining the fray to clear fiercely held bunkers. For the thousands of civilians who remained trapped in the crumbling city, this brought on a new level of horror, as they often found themselves sheltering in these same structures as they came under attack by American troops. Despite the hopelessness of the situation, orders from above came to remain defiant to the end, with the defenders and citizens of Aachen instructed to be “buried under the rubble” of the ancient city.

American troops and tanks cautiously advance along an Aachen street

On 19 October, Colonel Wilck issued his final orders to the remnants of his command in the city center:

“The defenders of Aachen will prepare for their last battle. Constricted to the smallest possible space, we shall fight to the last man, the last shell, the last bullet, in accordance with the Fuehrer’s orders.

In the face of the contemptible, despicable treason committed by certain individuals, I expect each and every defender of the venerable Imperial City of Aachen to do his duty to the end, in fulfillment of our Oath to the Flag. I expect courage and determination to hold out.

Long live the Fuhrer and our beloved Fatherland!”

Two days later, the Americans had reached Wilck’s command post in an above-ground air raid shelter on Lousbergstrasse in the north of the city, and despite the embattled Oberst’s fanatical dispatches to the OKW he knew the game was up. As the 155mm M12 was brought to bear on the bunker, two American POWs held in the headquarters were allowed to make for their lines under a white flag with Wilck’s offer to capitulate, which was taken to Brigadier General George Taylor, the assistant commander of the 1st Infantry Division. The surrender of Aachen was taken at 1205hrs on 21 October of 1944.

German prisoners are marched through the wrecked streets of Aachen after their surrender

The Stars and Stripes, when they were hoisted over Aachen, represented the first Allied flag to be raised over a German city. the First City to Fall had represented a tough, bloody battle with relatively little military value, but would leave valuable lessons to all involved. The capture of the capitol of the First Reich would serve as a marker for the nature of the conquest of the Third.

The ocean of ruins that used to be the captitol of the First Reich, with the husk of Charlemagne’s cathedral visible

The Commanders